One of the main reasons we started this project was because we were angry at the way the press was reporting on the migrant crisis in Europe – in particular, how the people in the Calais Jungle were being portrayed. We thought somebody needed to go to these places and give people a platform to tell their real stories. Well, it’s taken us so long to put this project together that we can no longer do that as the Calais Jungle has been closed down by the French Government. Keen to find out what happened to the people who were in the jungle and to learn more about the migrant crisis in general, we met up with Ivan and Fred from Utopia 56 in Paris.

Utopia 56 is a humanitarian organisation founded two years ago by volunteers in order to help give emergency aid to refugees in France. In its two years it has grown to be a large organisation of 8,000 volunteers who have racked up a total of 35,000 volunteering days.

First, we met up with Ivan, who coordinates all the work undertaken by Utopia in Paris. He gave us a bit more of an insight in to the migrant crisis in France and the work Utopia do to tackle it.

Q: Can you tell us a bit about the migrant crisis in Paris?

I think there are around 3,000 people living on the streets in Paris but it is very hard to say because there are people who have been here a long time and there are more and more coming every day. It is made harder because the government are trying to make the migrants invisible because President Macron said, “during the winter, nobody will sleep on the street”.

Q: What are these people at risk of on the streets?

It’s not just the traffickers [Previously to the interview we discussed how vulnerable people on the streets were at risk of being trafficked in to slavery]. They are at risk of death because it is that cold. They don’t have shelter, they don’t have blanket, they don’t have access to hospital. It is made worse because they don’t have rights like French people [as they don’t have the proper paperwork].

Q: What do Utopia 56 do to support refugees in France?

Originally, we were started as a team of volunteers to help clean the Calais Jungle. Now it is closed we work here in Paris as a humanitarian organisation. First, to try and provide refugees with first aid – shelter, warmth, access to hospital, food – then we also try to work with lawyers and social workers to get the most vulnerable people off the streets. But it is a very large issue and there is a lot of work. For example, I think, to get us through the winter we need at least 15,000 blankets.

Q: It’s clearly a huge issue and a lot of work – what drives you to keep doing it?

Shocked at the scale of the issue in Paris and at just how many refugees were on the streets, we were keen to speak to some of the people wrapped up in the crisis and tell their stories. Ivan hooked us up with an opportunity to watch the night shift at a humanitarian centre in Port de la Chappelle, we jumped at the chance and went to meet Fred who volunteers at the camp twice a week.

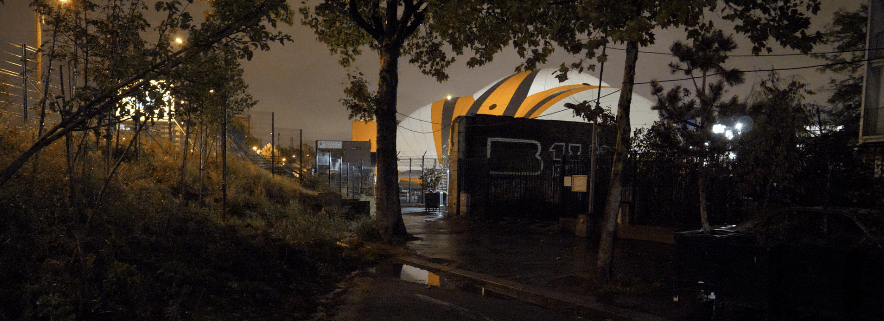

It was a really cold, really wet night in Paris and we arrived in Port de la Chappelle not knowing at all what to expect. What we found was what looked like an emergency aid camp straight out of a Hollywood blockbuster. It was the kind of thing you expect to see on the news in a war-torn country but it was in Paris, no more than 20 minutes from the Eiffel tower.

Outside of the camp there were people queuing trying to get in and inside there were people sitting around in the rain just waiting. It was late, it was freezing cold, soaking wet and there were families huddled together in temporary pop up tents at the foot of the dome (the central part of the camp). Fred was running the show and seemed to be on top of the chaos. He was exceptionally busy trying to help the hundreds of refugees that show up at the camp but we did manage to get a quick 5 minutes to ask him some questions about what was going on there.

He explained that the camp was just for men and ran by a different organisation but his job, and the job of Utopia, was to try and keep families who turned up there off the street and housed with volunteers. We stayed at the camp for a couple of hours and saw about 4 or 5 families go off with Utopia volunteers to be housed for the night. At the same time, we saw another family who, despite their best efforts, Fred and the team couldn’t find a roof for. They were given a cheap pop up tent and taken to the local park. We camped that night, with good gear, we were cold – they were a family of four, with young kids in a pop up tent that you’d find at Glastonbury.

Fred went on to explain how the camp now only allows people in who are found on the streets throughout the day so you can’t just turn up and gain access on the door. Outside the camp there are around 20-30 guys queuing at the railings, hoping to charm their way in. They couldn’t of course and they would be destined to fend for the themselves on the streets.

Fred then went on to tell us that if you get in to the camp then you will usually stay for a maximum of 10 days while the authorities try to find a solution for you and then after that you’re back on the streets. He also explained that when you enter the camp for the first time you get taken to a kind of shop where you can pick a new outfit. Apparently, almost everyone spends hours, sorting through and trying on different clothes – they spend so long because for many it’s the first choice they’ve had in months.

We stayed at the camp for a couple of hours and chatted to a couple of refugees who had managed to get in but we were unable to film any stories. They were afraid of what might happen to them as a result of how they had been treated for talking to press at previous camps along the way. One guy said he had been beaten at a camp elsewhere in Europe so the authorities could be sure he didn’t say anything bad about the conditions. Feeling like we were mainly getting in the way, we left the camp about 10pm. Fredrick was staying long in to the night to try and help people who might turn up. We asked him why he does it:

The situation in Paris was really scary. Never have we witnessed a more real representation of the huge inequalities in our society. We went from seeing genuine suffering and struggle in Port de la Chapelle and within 20 minutes found ourselves taking selfies with friends in front of the Eiffel Tower.

The migrant crisis is an absolute gold mine for traffickers. It creates huge numbers of vulnerable people who are easily coerced or forced in to a life of slavery. We’re going to try and continue tracking the migrant crisis as we head down through the rest of Europe and in to Africa. Hopefully, we’ll be able to share some stories of the people we meet along the way and give some indication of what we can do to help the situation back home.

You can learn more about the situation in Paris by visiting Utopia 56’s website where you can also donate to their work or enquire about volunteering yourself – http://www.utopia56.com.

Post on the board